There is a simple template script writers use to plot their stories. It’s called the three-act structure, and it’s a great method that can help you plot your books.

Not all writers create the same. George R.R. Martin once said there are two types of writers – a gardener and an architect. A gardener will plant some seeds and will watch to see what grows, whereas the architect will plan everything.

I am an architect. I like to know where the story is going, because I would run dry if I didn’t. Well, my first draft is plotted. When working on the second draft I change a lot of stuff – The Six Hands of Fate: Book 1 was rewritten three times until I got the story I wanted. I let my characters drive the later drafts, often changing the plot to suit their personalities.

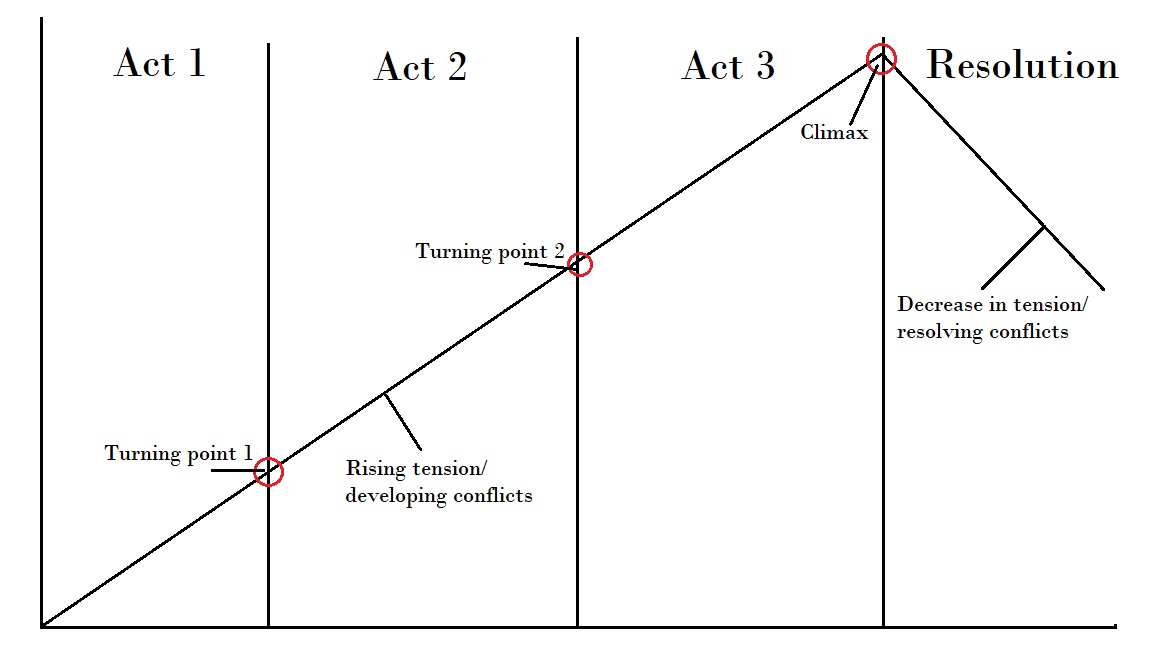

I use the three-act structure to help me keep an eye on my evolving conflicts, which steer the story. It looks like this:

It’s simple, no? No? OK, well, Act 1 is your set up. This is where you introduce your characters, their goals and what is keeping them from getting what they want (or conflicts). Act 2 is where those conflicts really start to get in the way, or further conflicts are introduced. In Act 3 the conflicts reach their climax. The Resolution is the bit at the end that ties up the loose ends, and gives the reader a chance to slump in relief (or weep in misery).

As I said, it is used mostly in script writing. If you have any Disney or Pixar DVDs to hand, pick one at random and run through the plot in your head. I will guarantee it follows the above pattern.

Here’s an example of how Up works against this structure (if any of you out there are mad enough not to have watched Up already, look away now because spoilers – and then go buy/rent a copy):

Act 1

Carl Fredricksen’s goal is established – he and his wife, Ellie, want to go to Paradise Falls. Unfortunately life gets in the way and they don’t make it. Ellie dies, leaving their promise unfulfilled (“Cross your heart”).

The tension rises to the first turning point. Alone, the sweet Carl we grew to love has turned into a grouchy old man who refuses to leave his house while a city grows up around him. The conflict that he could lose his house is established.

We also meet Russell, which establishes a new conflict of Carl’s relationship with the Wilderness Explorer.

The turning point of Act 1 into Act 2 starts when Carl’s mailbox is knocked down by a reversing truck and he ends up hitting a construction worker on the head with his cane. Carl now has to leave his house. A time limit is introduced – he has to leave the next day, prompting a need for action. This is his last chance to fulfil his promise to Ellie. He modifies his house with balloons, which he releases as the retirement home guys come to pick him up. Turning point 1 finishes as the house takes off.

Act 2

As the house ascends into the air, we enter Act 2, and the arrival at Paradise Falls sets the scene for the rest of the story. We have a new time limit – Carl has three days to get the house to the falls before the helium in the balloons runs out.

Carl and Russel’s conflict comes into full play. Carl wants to get to the falls as quickly as he can, but Russell doesn’t want to walk anymore and constantly needs to stop to take a dump.

And then Kevin’s conflict comes into play. This one is more complex and involves quite a few characters. We know from Act 1, from the film young Carl watches in the cinema, that Charles Muntz is out to capture a large bird after being accused of forgery. And a coincidence gets Carl into trouble, because Russell finds the very bird Charles is out to get. Carl gets dragged into Charles’s obsession to capture it.

Act 2 draws to a close as Carl, Russell and Doug are captured by Alpha, Beta and Gamma, and taken to The Spirit of Adventure.

The turning point for Act 2 into Act 3 starts when Kevin, sitting on the top of the house outside The Spirit of Adventure, calls out to her babies in the labyrinth, alerting Charles and the dogs that she is there. This begins the chase scene, which leads to Charles being able to track down and capture Kevin.

Act 3

All the conflicts reach their climatic points.

With the house now at Paradise Falls, Carl’s promise to Ellie is fulfilled. But in order to achieve his goal – or save his house after Charles sets it on fire – he had to turn his back on Kevin, meaning she was captured.

This then makes the conflict between Carl and Russell reach its climax, because Russell doesn’t understand why the house is so important to Carl. To Russell, reuniting Kevin with her babies is the most important thing. So he leaves Carl.

We now begin the final show down. Having realised his mistake – that getting the house to Paradise Falls was insignificant, because the adventure he and Ellie had as a married couple was the only adventure they needed – Carl goes after Russell.

Act 3 is all action, which resolves the conflicts. The bird conflict is resolved when Charles plunges to his death from the top of his ship, and then Kevin is reunited with her babies.

Carl’s personal conflict – keeping his promise to Ellie – is further resolved as he watches their house sink below the clouds. He’s achieved his dream, even if it didn’t give him the fulfilment he thought it might. After all, you have to live for the living, not the dead.

Resolution

With Carl’s goal complete – at least to his satisfaction – and Kevin no longer in danger, the final threads of Carl and Russell’s conflict draw to a close as Carl pins on Russell’s badge at his Wildness Explorer ceremony. Russell has assisted the elderly and Carl gets to experience having the child he and Ellie were unable to have. Russell’s dream of being able to return to that curb outside the ice cream shop, and count the red and blue cars is also resolved.

Unknown to Carl, the house made it back to the falls, so he kept his promise to Ellie after all.

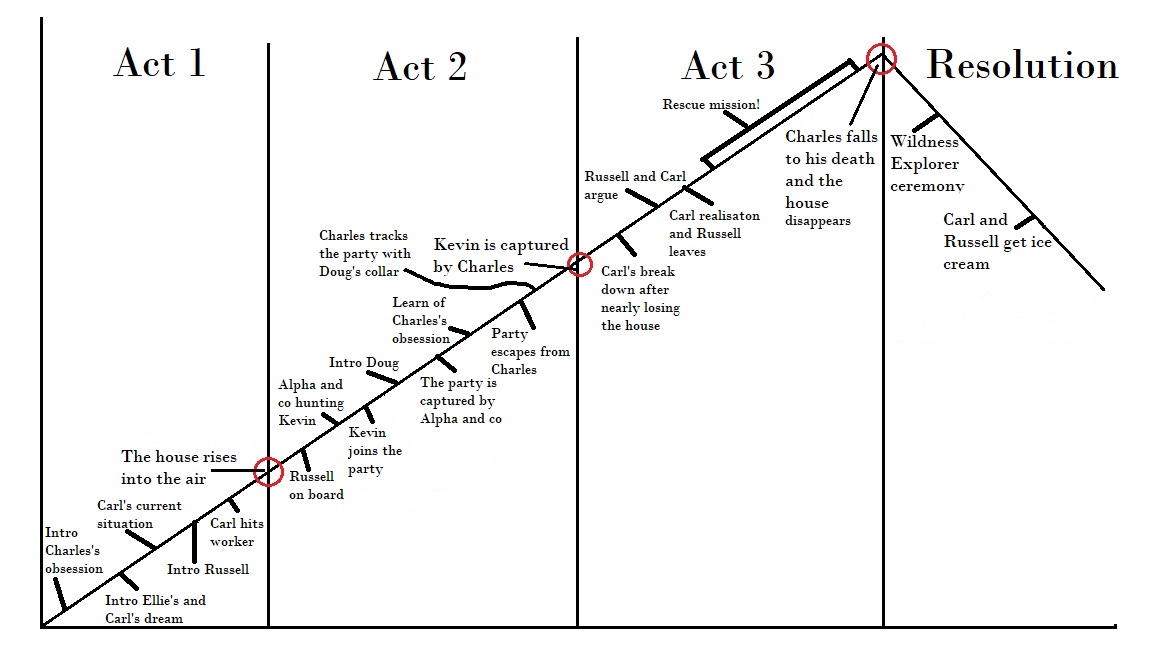

If you were to put Up‘s plot into the three-act structure graph, it would look something like this:

I have missed some conflicts out. There’s Doug’s and Russell’s personal growths – Doug goes from the bottom to the top of the pack, and Russell’s confidence grows throughout the film. If you’re planning your own book, then you could do tension graphs for each conflict so you can go into more detail about each one, but it depends on how naturally you want your story to progress.

Nice, huh? Simple, huh? The three-act structure isn’t a golden rule – you don’t have to follow it – but I think it makes it easier to create successful stories.

Before Christmas I watched Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai and disliked it, because I felt the story lost its natural progression. It went off on a tangent towards the end and didn’t follow the three-act structure – I felt the main character had no goal and the story lost focus of what it was about. A shame, because all of Mamoru Hosoda’s previous films (Summer Wars, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, The Beast and the Boy) have all been amazing (and have followed that three-act structure).

“But these are films!” I hear you cry. “And I’m writing a book! They’re not the same!” No, they’re not, but at the same time I think they are. They’re just different ways in which you can present a story – like oil paints and water colours.

Books tend to have a looser structure. Disney and Pixar films are around one and a half hours long, which is 30 mins for each act. But with books you have a more fluid structure.

I had a quick look at Alice Oseman’s I Was Born for This, and found her turning point (when Angel and Jimmy get shoved in a toilet together at the meet and greet) didn’t happen until halfway through the book – act 1 was a lot longer than acts 2 and 3.

The three-act structure is not limiting. For epics, you can give your books more than three acts (think Brandon Sanderson’s The Way of Kings books, which have, like, 5 acts each?!). The three-act structure is also super helpful when plotting trilogies, or series in general, as you can use one act to represent a book.

The three-act structure is helpful, but remember it’s not limiting. It’s the skeleton to hang your story on.

Does your WIP fit into the three-act structure? Comment down below. Let me know,